(AI-assisted writing in progress)

Pulp Fiction and Women’s Fashion — A Symbiosis of Desire, Danger, and Liberation

Pulp fiction was born from the coarse fibers of cheap wood pulp and the feverish dreams of mass imagination. In the first half of the 20th century, these lurid magazines—bursting with sensational tales of crime, adventure, and forbidden romance—were sold for a dime, yet they shaped an entire century of visual and emotional culture. Among their most enduring contributions lies an unexpected relationship: the deep, intertwined evolution of pulp fiction and women’s fashion.

1. The Visual Language of Desire

Open any issue of Amazing Stories or Detective Tales from the 1930s or 1940s, and the cover will almost always reveal a woman in peril—or power. Tight satin dresses cling to the figure, seams bursting with tension; skirts are torn, lipstick smudged, and eyes wide with either fear or defiance. To the casual viewer, these images may appear as simple tools of male fantasy. But in their repetition, exaggeration, and boldness, they also encoded the shifting role of women in modern society.

Fashion here became narrative armor: a weaponized form of allure. The short skirts and plunging necklines did not merely titillate; they symbolized the breaking of Victorian restraint, a visual shorthand for modern womanhood’s entry into danger, autonomy, and spectacle. In the pulp universe, clothes were never just clothes—they were metaphors for desire’s volatility, for the body’s rebellion against propriety.

2. The Femme Fatale as Cultural Prototype

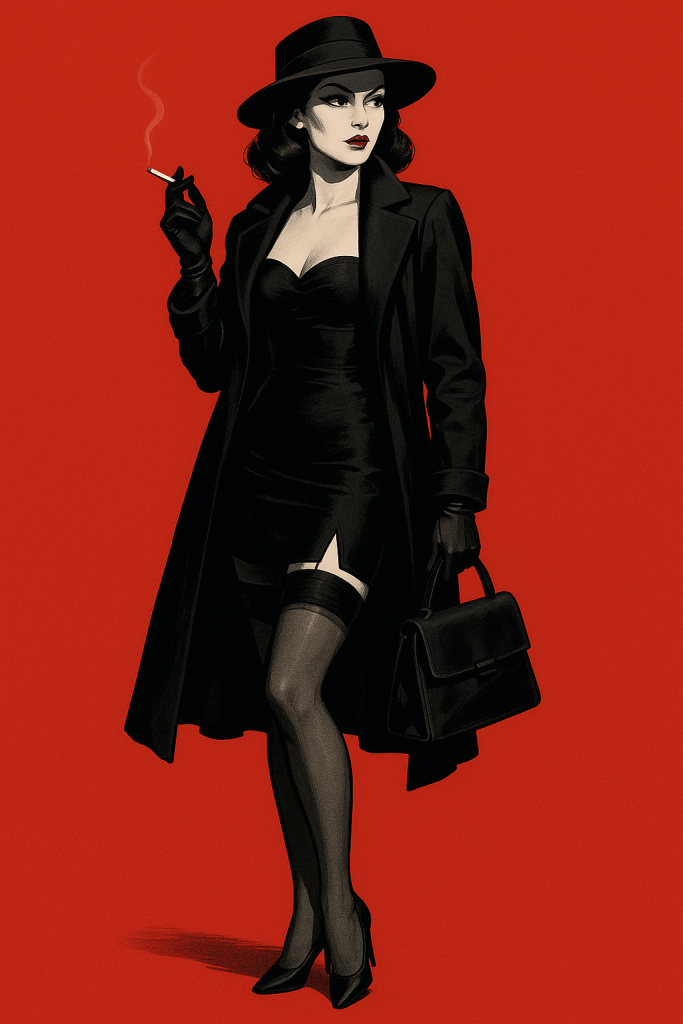

By the 1940s and 1950s, pulp fiction merged into the cinematic universe of film noir, and the “femme fatale” emerged as its reigning archetype. Her trench coat, silk gloves, and daggered heels became emblems of both seduction and death. She was neither the submissive muse nor the pure victim—she was the narrative catalyst. In this evolution, fashion became a grammar of control: the way a woman held her cigarette, adjusted her hat, or crossed her legs became a cinematic sentence of domination.

Designers noticed. The fashion world absorbed these silhouettes—sharp shoulders, nipped waists, dramatic contrasts of light and shadow—and transformed them into the couture of rebellion. Christian Dior’s “New Look” and later Yves Saint Laurent’s “Le Smoking” suit owe more to the pulp aesthetic than history often admits. The femme fatale taught fashion that darkness sells—and that a woman in black could command the entire frame.

3. From Page to Street: The Democratization of Style

Pulp’s influence did not vanish with the magazines’ decline; it mutated. By the 1970s, pulp-inspired aesthetics—bold colors, exaggerated femininity, and ironic self-awareness—reappeared in underground comics and punk fashion. The distressed leather jacket, fishnet stockings, and glossy red lips became symbols of working-class defiance and erotic independence. The same visual tropes once confined to pulp illustrations were now worn proudly on the streets of New York and London.

In this sense, pulp fiction anticipated fashion’s postmodern turn. It blurred the boundary between “cheap” and “chic,” between mass fantasy and personal identity. The pulp heroine’s theatricality—her knowing gaze, her exaggerated curves—became the prototype for the self-styled modern woman, who constructs her persona through irony, boldness, and self-possession.

4. The Cultural Afterlife of the Pulp Woman

Today, the legacy continues in the aesthetics of Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, in fashion editorials shot like crime covers, in perfume ads that trade on noir mystery. The pulp woman—once dismissed as a disposable fantasy—has become a cultural archetype of power. Her wardrobe, born from sensationalism, now adorns galleries, catwalks, and Instagram feeds.

Thus, the relationship between pulp fiction and women’s fashion is not merely visual but ideological. Both industries commodified desire, yet both also offered subversive possibilities: a space where women could rehearse autonomy through image. Beneath the lurid colors and melodramatic poses lies something radical—the recognition that style itself can be narrative, and that even on the cheapest paper, a woman’s silhouette could rewrite the story of modern freedom.

Please leave your thoughts and critiques in the comments section.

Leave a comment